Curves of Competence

In this post, I will introduce a new concept that I have been synthesizing and thinking about for a few months now. It is a useful mental model that has helped me answer several questions I have had in the past about knowledge, expertise, and learning.

It is called Curves of Competence.

But first, let me introduce a known concept called Circle of Competence.

Circle of Competence

Warren Buffett wrote about the Circle of Competence in his 1996 shareholder letter.

Should you choose, however, to construct your own portfolio, there

are a few thoughts worth remembering. Intelligent investing is not

complex, though that is far from saying that it is easy. What an

investor needs is the ability to correctly evaluate selected businesses.

Note that word "selected": You don't have to be an expert on every

company, or even many. You only have to be able to evaluate companies

within your circle of competence. The size of that circle is not very

important; knowing its boundaries, however, is vital.

They key point here is that you want to know what is in your competence, and what is not. For example, computer science and artificial intelligence is in my circle of competence, but history and philosophy are not.

Curves of competence

Circle of competence is already very useful and helps you to understand what you know vs. what you don’t. But what it doesn’t tell you is how much you know something.

Instead of a circle, you can imagine a mountain with a circular base. When looking from the top, you see a circle, which corresponds to the circle of competence, and the height corresponds to how much you know the subject.

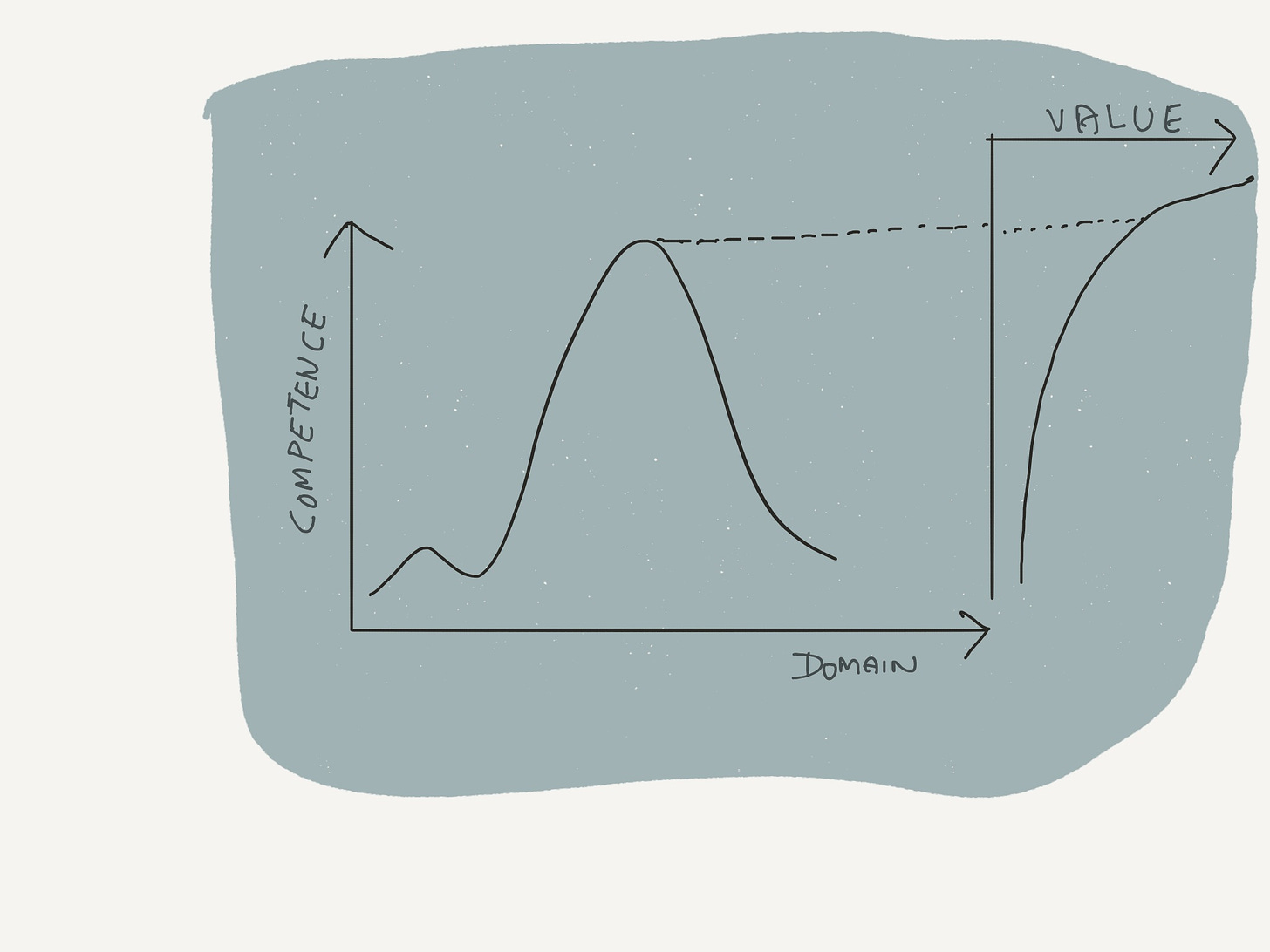

3D is always tricky to imagine, so let's make this simpler and visualize it in 2D, and come up with curves of competence as below.

So the peaks correspond to the topics where you are the most competent. Flat regions are where you are least competent.

The peak matters a lot

The peak is what makes you an expert. I know how to invest1 and so does Warren Buffett. But Buffett’s peak is a lot taller than mine.

Another interesting aspect is that the value of your expertise (e.g. how much money you can make, or how much fame and following you can attract etc.) is exponentially related to the peak.

That’s why some people can make 10x more salaries than others. And that’s why Warren Buffett is worth so much more than others (his peak is not a million times taller than mine).

Growing the peak

Don’t fool yourselves into thinking that it is easy to increase the peak. If you are staring out flat, it is relatively easy to add some height. Think of learning tennis. You get better quickly, but you end up hitting a plateau. After that, increasing the peak is a very hard and deliberate activity and involves a lot of deliberate practice.

Spill over

As you visualize increasing the peak, you will realize adjacent areas get taller as well. You can imagine this as adding more mass to the mountain: it is very difficult to keep increasing the height of one particular region without touching others. But that’s the point: you have learn many different adjacent skills as well and that’s what provides support for you to increase your core expertise.

What others see

People notice your peak. The taller it is, the more people can see. They will then want to come work with you, or refer you to others etc. And before you know, you are able to work with other top-notch talent, and this helps you increase your peak even more. That’s a good virtuous cycle to have.

Width plays a role

If you are starting out, it is very useful to explore and learn a diverse set of subjects, and increase your overall width. In Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, David J. Epstein makes a compelling argument for why specialization early on is not such a good idea. He writes

The psychologists highlighted the variety of paths to excellence, but the most common was a sampling period, often lightly structured with some lessons and a breadth of instruments and activities, followed only later by a narrowing of focus, increased structure, and an explosion of practice volume.

Establishing the curve

There will invariably a disconnect between the actual hill, vs. your perceived shape of the hill. This is due to the Dunning Kruger effect. You may think that there are some peaks while they are not that peaky.

Using Curves of Competence to figure out what to learn

You can add mass to the hill across all domains or you can focus on making a few peaks taller. They both have different payoffs. I personally thinking it is important to do both, rather than just one: take a few peaks that are important to you and relentlessly focus on making them taller, and then add as much breadth as possible.

And there you go, that’s my new idea. Please let me know what you think!

Yes this is debatable.